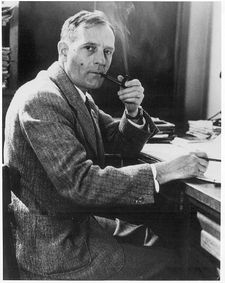

Edwin Hubble

| Edwin Powell Hubble | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 20, 1889 Marshfield, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | September 28, 1953 (aged 63) San Marino, California |

| Residence | United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | University of Chicago Mount Wilson Observatory |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago University of Oxford |

| Known for | Big Bang Hubble's law Redshift Hubble sequence |

| Influenced | Allan Sandage |

| Notable awards | Bruce Medal 1938 |

Edwin Powell Hubble (November 20, 1889 – September 28, 1953) was an American astronomer who profoundly changed our understanding of the universe by demonstrating the existence of galaxies other than our own, the Milky Way. He also discovered that the degree of "Doppler shift" (specifically "redshift") observed in the light spectra from other galaxies increased in proportion to a particular galaxy's distance from Earth. This relationship became known as Hubble's law, and helped establish that the universe is expanding. Hubble has sometimes been incorrectly credited with discovering the Doppler shift in the spectra of galaxies, but this had already been observed earlier by Vesto Slipher, whose data Hubble used.

Contents |

Biography

Edwin Hubble was born to an insurance executive in Marshfield, Missouri, and moved to Wheaton, Illinois, in 1889. In his younger days he was noted more for his athletic prowess than his intellectual abilities, although he did earn good grades in every subject except for spelling. He won seven first places and a third place in a single high school track & field meet in 1906. That year he also set the state high school record for the high jump in Illinois. Another of his personal interests was dry-fly fishing, and he practiced amateur boxing as well[1].

His studies at the University of Chicago concentrated on mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy, which led to a bachelor of science in 1910. Hubble also became a member of the Kappa Sigma Fraternity (and in 1948 was named the Kappa Sigma "Man of the Year"). He spent the three years after earning his bachelors as one of Oxford University's first Rhodes Scholars, studying jurisprudence initially, then switching his major to Spanish and earning his master's degree in that field. Some of his acquired British mannerisms and dress stayed with him all his life, occasionally irritating his American colleagues.

Upon returning to the United States, Hubble taught Spanish, physics, and mathematics at the New Albany High School in New Albany, Indiana. He also coached the boy's basketball team there. Hubble earned admission as a member of the Kentucky bar association, although he reportedly never actually practiced law in Kentucky.[2] Hubble served in the U.S. Army in World War I, and he quickly advanced to the rank of major. He returned to astronomy at the Yerkes Observatory of the University of Chicago, where he received his Ph.D. in 1917. His dissertation was titled Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae.

In 1919, Hubble was offered a staff position in California by George Ellery Hale, the founder and director of the Carnegie Institution's Mount Wilson Observatory, near Pasadena, California, where he remained on the staff until his death. Hubble also served in the U.S. Army at the Aberdeen Proving Ground during World War II. For his work there he received the Legion of Merit award. Shortly before his death, Mount Palomar's giant 200-inch (5.1 m) reflector Hale Telescope was completed, and Hubble was the first astronomer to use it. Hubble continued his research at the Mount Wilson and Mount Palomar Observatories, where he remained active until his death.

Hubble died of a cerebral thrombosis (a spontaneous blood clot in his brain) on September 28, 1953, in San Marino, California. No funeral was held for him, and his wife, Grace Hubble, did not reveal the disposition of his body.[3][4]

Discoveries

The Universe goes beyond the Milky Way galaxy

Edwin Hubble's arrival at Mount Wilson, California, in 1919 coincided roughly with the completion of the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker Telescope, then the world's largest telescope. At that time, the prevailing view of the cosmos was that the universe consisted entirely of the Milky Way Galaxy. Using the Hooker Telescope at Mt. Wilson, Hubble identified Cepheid variables (a kind of star; see also standard candle) in several spiral nebulae, including the Andromeda Nebula. His observations, made in 1922–1923, proved conclusively that these nebulae were much too distant to be part of the Milky Way and were, in fact, entire galaxies outside our own. This idea had been opposed by many in the astronomy establishment of the time, in particular by the Harvard University-based Harlow Shapley. Hubble's discovery, announced on January 1, 1925, fundamentally changed the view of the universe.

Hubble also devised the most commonly used system for classifying galaxies, grouping them according to their appearance in photographic images. He arranged the different groups of galaxies in what became known as the Hubble sequence.

Redshift increases with distance

Combining his own measurements of galaxy distances based on Henrietta Swan Leavitt's period-luminosity relationship for Cepheids with Vesto Slipher's measurements of the redshifts associated with the galaxies, Hubble and Milton L. Humason discovered a rough proportionality of the objects' distances with their redshifts. Though there was considerable scatter (now known to be due to peculiar velocities), Hubble and Humason were able to plot a trend line from the 46 galaxies they studied and obtained a value for the Hubble-Humason constant of 500 km/s/Mpc, which is much higher than the currently accepted value due to errors in their distance calibrations. In 1929 Hubble and Humason formulated the empirical Redshift Distance Law of galaxies, nowadays termed simply Hubble's law, which, if the redshift is interpreted as a measure of recession speed, is consistent with the solutions of Einstein’s equations of general relativity for a homogeneous, isotropic expanding space. Although concepts underlying an expanding universe were well understood earlier, this statement by Hubble and Humason led to wider scale acceptance for this view. The law states that the greater the distance between any two galaxies, the greater their relative speed of separation.

This discovery was the first observational support for the Big Bang theory which had been proposed by Georges Lemaître in 1927. The observed velocities of distant galaxies, taken together with the cosmological principle appeared to show that the Universe was expanding in a manner consistent with the Friedmann-Lemaître model of general relativity. In 1931 Hubble wrote a letter to the Dutch cosmologist Willem de Sitter expressing his opinion on the theoretical interpretation of the redshift-distance relation:[5]

[W]e use the term 'apparent velocities' in order to emphasize the empirical feature of the correlation. The interpretation, we feel, should be left to you and the very few others who are competent to discuss the matter with authority.

Today, the 'apparent velocities' in question are understood as an increase in proper distance that occurs due to the expansion of space. Light traveling through stretching space will experience a Hubble-type redshift, a mechanism different from the Doppler effect (although the two mechanisms become equivalent descriptions related by a coordinate transformation for nearby galaxies).

In the 1930s Hubble was involved in determining the distribution of galaxies and spatial curvature. These data seemed to indicate that the universe was flat and homogeneous, but there was a deviation from flatness at large redshifts. According to Allan Sandage,

Hubble believed that his count data gave a more reasonable result concerning spatial curvature if the redshift correction was made assuming no recession. To the very end of his writings he maintained this position, favouring (or at the very least keeping open) the model where no true expansion exists, and therefore that the redshift "represents a hitherto unrecognized principle of nature."[6]

There were methodological problems with Hubble's survey technique that showed a deviation from flatness at large redshifts. In particular the technique did not account for changes in luminosity of galaxies due to galaxy evolution.

Earlier, in 1917, Albert Einstein had found that his newly developed theory of general relativity indicated that the universe must be either expanding or contracting. Unable to believe what his own equations were telling him, Einstein introduced a cosmological constant (a "fudge factor") to the equations to avoid this "problem". When Einstein heard of Hubble's discovery, he said that changing his equations was "the biggest blunder of [his] life".[7]

Other discoveries

Hubble discovered the asteroid 1373 Cincinnati on August 30, 1935. He also wrote The Observational Approach to Cosmology and The Realm of the Nebulae around this time.

Nobel Prize

Hubble spent much of the later part of his career attempting to have astronomy considered an area of physics, instead of being its own science. He did this largely so that astronomers — including himself — could be recognized by the Nobel Prize Committee for their valuable contributions to astrophysics. This campaign was unsuccessful in Hubble's lifetime, but shortly after his death the Nobel Prize Committee decided that astronomical work would be eligible for the physics prize.[8]

On March 6, 2008, the United States Postal Service released a 41 cent stamp honoring Hubble on a sheet titled "American Scientists." His citation reads: "Often called a 'pioneer of the distant stars,' astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889-1953) played a pivotal role in deciphering the vast and complex nature of the universe. His meticulous studies of spiral nebulae proved the existence of galaxies other than our own Milky Way. Had he not died suddenly in 1953, Hubble would have won that year's Nobel Prize in Physics." The other scientists on the "American Scientists" sheet include Gerty Cori, biochemist; Linus Pauling, chemist; and John Bardeen, physicist.

Honors

Awards

- Bruce Medal in 1938.

- Franklin Medal in 1939.

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1940.

- Legion of Merit for outstanding contribution to ballistics research in 1946.

Named after him

- Asteroid 2069 Hubble.

- The crater Hubble on the Moon.

- Orbiting Hubble Space Telescope.

- Edwin P. Hubble Planetarium, located in the Edward R. Murrow High School, Brooklyn, NY.

- Edwin Hubble Highway, the stretch of Interstate 44 passing through his birthplace of Marshfield, Missouri

- The Edwin P. Hubble Medal of Initiative is awarded annually by the city of Marshfield, Missouri - Hubble's birthplace

- Hubble Middle School in Wheaton, Illinois—renamed for Edwin Hubble when Wheaton Central High School was converted to a middle school in the fall of 1992.

- 2008 "American Scientists" US stamp series, $0.41

See also

- Astronomy

- Distance measures

- Cosmic distance ladder

- Galaxies

- Hubble sequence

- Galaxy morphological classification

- Gerard de Vaucouleurs

- William Wilson Morgan

- Expansion of the universe

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Edwin Hubble House, residence and National Historic Landmark in San Marino, California

- The Great Debate of 26 April 1920

References and notes

- ↑ World of Physics and The Cloudy Night Book

- ↑ Who Was Edwin Hubble?

- ↑ "Edwin Hubble". Makara. http://www.makara.us/04mdr/01writing/03tg/bios/Hubble.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ A Short History of Nearly Everything, Bill Bryson

- ↑ Galaxy redshifts reconsidered - The Astronomy Cafe, Dr. Sten Odenwald

- ↑ Sandage, Allan (1989), "Edwin Hubble 1889-1953", The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 83, No.6. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Cosmological Constant from Stephen Hawking's Universe on PBS

- ↑ Astroprof's article on Hubble

Further reading

- Christianson, Gale; Edwin Hubble: Mariner of the Nebulae Farrar Straus & Giroux (T) (New York, August 1995.)

- Hubble E.P., The Observational Approach to Cosmology (Oxford, 1937.)

- Hubble E.P., The Realm of the Nebulae (New Haven, 1936.)

- Hubble, Edwin (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". PNAS 15 (3): 168–173. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/15/3/168.

- Mayall, N.U., EDWIN POWELL HUBBLE BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS NAS 41

- Osterbrock, Donald E.; Joel A. Gwinn and Ronald S. Brashear (July 1993). "Edwin Hubble and the Expanding Universe". Scientific American 269 (1): 84–89. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0793-84.

- Harry Nussbaumer and Lydia Bieri, Discovering the expanding universe. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

External links

- Time 100 Profile

- Astronomy at the University of Louisville - Photographs of Edwin Hubble at New Albany High School.

- Edwin Hubble bio - Written by Allan Sandage

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Edwin Hubble", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Hubble.html.

- American Physical Society's Hubble Bio

- Edwin Powell Hubble - The man who discovered the cosmos

- Astroprof's article on Hubble

- Hubble: The Man and His Telescope - slideshow by Life magazine

|

||||||||